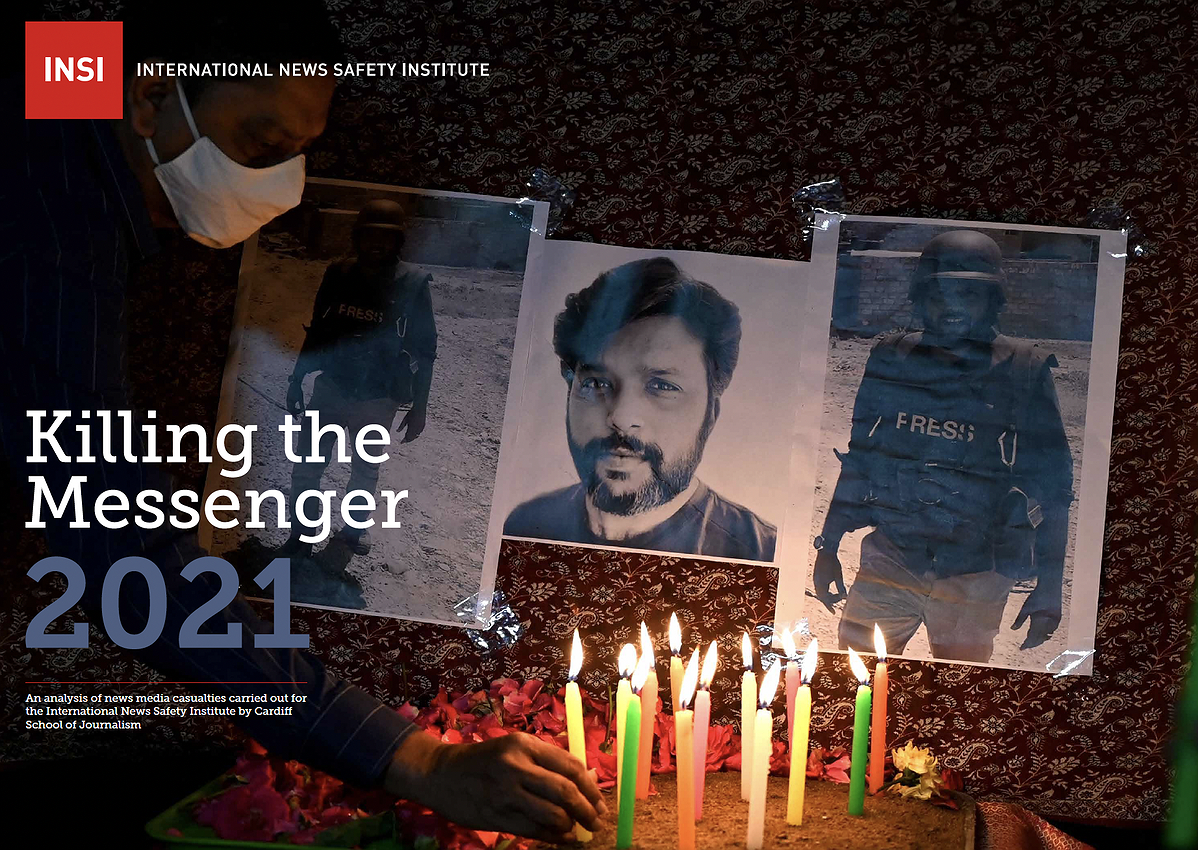

Mexico tops the list again in INSI's annual report of media casualties, Killing the Messenger 2021.

Every year at INSI we publish the grim total of journalist deaths around the world. Yet, from the remotest town in Afghanistan, to the heart of Europe, the casualty number itself is not enough to show the impact of each and every one of these deaths on the societies those journalists were serving through their work.

On the first day of 2021, after visiting family in a village nearby, Bismillah Adel Aimaq and his brother were driving back home to Firozkoh, a remote mountain town, high up on the western slopes of the Hindukush mountain range. At just 28 years of age, the bright and handsome Bismillah was the editor-in-chief of the Voice of Ghor, a local private radio station in a severely underdeveloped mountainous province, almost entirely reliant on agriculture and animal husbandry. In a region where deadly land disputes and marrying off young daughters for cattle are still common, Bismillah’s journalism and championing of human rights had earned him repeated death threats, yet no police protection. As the young married journalist drove home, in the afternoon of New Year’s Day, a group of gunmen ambushed his car and shot and killed him, still at the wheel. They then fled, leaving behind his unharmed brother and little doubt that this was a targeted assassination. One must stop and think of the devastating impact that such a killing would have had, not only on Bismillah’s family and his radio station, but also on a community otherwise so cut off from the rest of the country, let alone the rest of the world. It’s hard to imagine many young people in Ghor being willing to follow in Bismillah’s steps now, and trying to bring news and progress to their homeland. And who could possibly blame them?

Seven months later, and seven thousand kilometres away, Peter de Vries, the Netherlands’ best known crime journalist, was shot five times by a masked gunman, a hitman for a brutal drug syndicate de Vries had taken a stand against. The 64-year-old journalist had just appeared on national television, and was walking back to his car in broad daylight on one of Amsterdam’s busiest streets. The country was stunned by the brazenness of the attack, the latest in a series of acts of terror, against both the media and the judiciary, that authorities appear unable to stop, leading to talk of a parallel narco-state. For a country ranking sixth in the World Press Freedom Index, it is extraordinary that today’s Dutch crime reporters should feel under threat when they cover certain trials and that newsrooms should feel the need to rotate reporters on a story- to make sure no individual journalist is singled out by the mob.

Every one of the fifty-six journalists’ deaths in 2021 is a personal tragedy but also an indictment for the country that allowed it to happen. Mexico, for the third year running, came top of the list for journalists’ casualties, with nine colleagues violently killed, in a clear sign that the country’s government continues to afford organised crime utter impunity for such attacks. Afghanistan maintained its place as the second deadliest country for journalists. 2021 has also seen the largest loss of life ever among Afghan female journalists. Three were shot in near-simultaneous attacks, possibly orchestrated by IS, while on their way home from work in Jalalabad. The fourth, 23 year old newsreader Mina Khairi, was blown up in her car as she was out shopping with her mother. It is a cruel paradox that this high toll might in fact reflect the growing role women were acquiring in Afghan media and society in general, before the Taliban takeover.

Conflict and civil strife have killed two journalists each in Ethiopia, Myanmar and Azerbaijan and, in the Philippines, the same year in which Maria Ressa shared a hugely deserved Nobel Peace Prize, no less than three of her Filipino colleagues were shot dead.

Fears that the threat posed to journalists by Islamic extremism was spreading to sub-Saharan Africa were confirmed when two seasoned Spanish filmmakers, David Beriáin and Roberto Fraile, were killed in an ambush by an IS franchise group in Burkina Faso, while making a documentary about wildlife poachers.

And journalists also lost their lives because of their job in 17 more countries, from India to Nigeria, with the vast majority of these cases not having seen any proper investigation, or legal proceedings whatsoever.

Back in Afghanistan, we mourned the loss of one of our own colleagues, an INSI member. Reuters’ Pulitzer prize winning photojournalist Danish Siddiqui was among the best trained, most experienced and better equipped journalists to cover conflict anywhere. But even with the best mitigation measures in place, it is impossible to cover the frontlines of war without any risk. A few weeks before his final and fatal assignment, Danish asked his picture editor at Reuters a rhetorical question “If we don’t go, who will?’. No story is worth losing one’s life but we should all be grateful to those journalists who’ve stepped up in 2021, to bear witness to injustices small and big, or as in Danish’s case, to history in the making. - Elena Cosentino, INSI director

Read Killing the Messenger here.